Om Andreas Cervenkas bok Girig-Sverige i Sydsvenskan

Skriver om Andreas Cervenkas bok Girig-Sverige i Sydsvenskan. Min kanske viktigaste poäng:

Det mest problematiska i boken är att ojämlikhet beskrivs som ett problem oavsett hur den har uppstått. Det förhållningssättet bortser nämligen från procedurers stora betydelse. Har de rika blivit rika genom legitima transaktioner och frivilliga byten, genom tur och tillfälligheter eller genom korruption och rofferi? Detta spelar roll, både för människors uppfattningar om hur rättvis fördelningen är, och för samhällets totala välståndsnivå.

En annan poäng är att välfärdsstaten innebär att människors behov av eget sparande minskar. Många skulle nog se det som en av välfärdsstatens finesser, men det ökar också förmögenhetsojämlikheten.

Sveriges ojämna förmögenhetsfördelning är delvis en konsekvens av den svenska välfärdsstaten. Tack vare den behöver de flesta inte ha en privat förmögenhet för att hantera oväntade vårdbehov, inkomstbortfall och försörjning på ålderns höst.

Argumentet jag anför är teoretiskt, men det finns empirisk evidens. Här skriver Cato om frågan. Här är ett ECB-working paper i vars abstract följande står att läsa:

multilevel cross-country regressions show that the degree of welfare state spending across countries is negatively correlated with household net wealth. These findings suggest that social services provided by the state are substitutes for private wealth accumulation and partly explain observed differences in levels of household net wealth across European countries. In particular, the effect of substitution relative to net wealth decreases with growing wealth levels. This implies that an increase in welfare state spending goes along with an increase - rather than a decrease - of observed wealth inequality

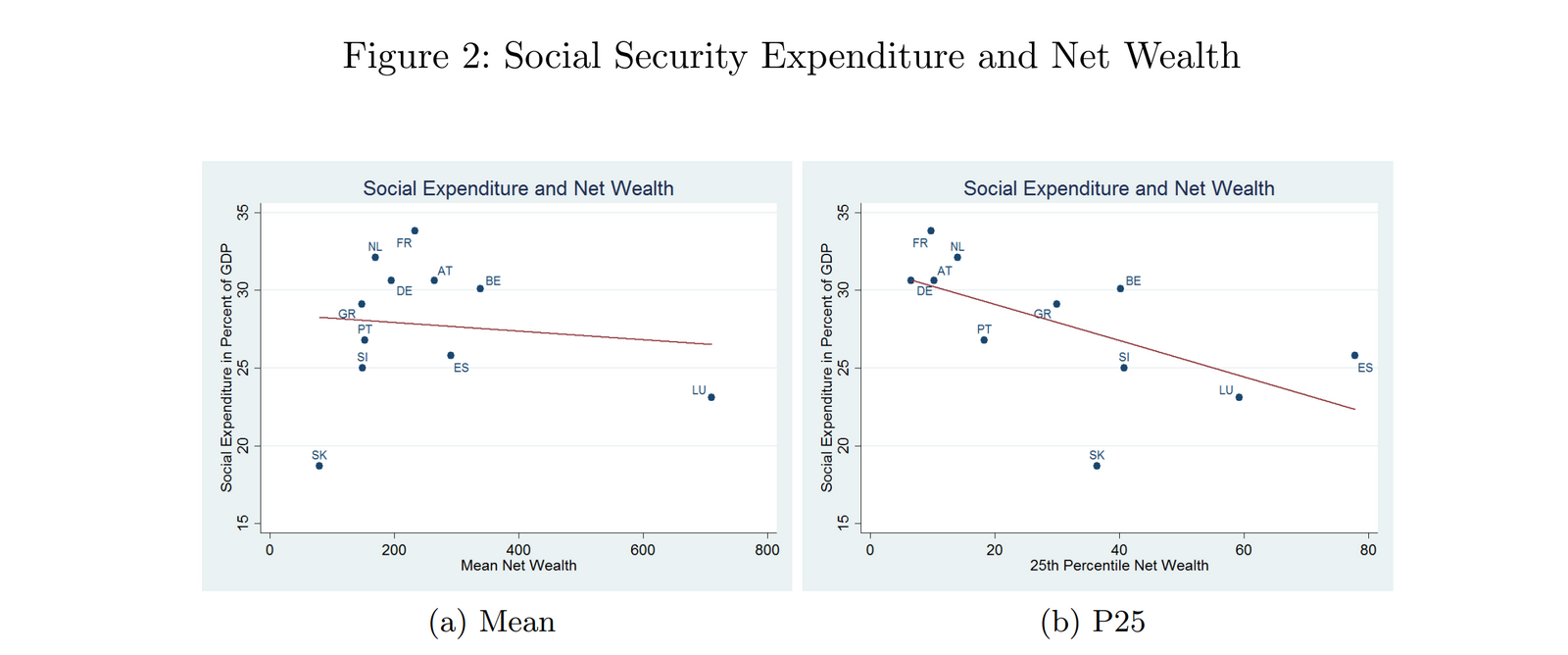

En illustrativ figur ur pappret:

Slutligen är det värt att uppmärksamma den i mina ögon relativt skakiga metoden som Credit Suisse använder. Så här beskrivs den [något nedkortat]

The first step establishes the average level of wealth for each country. The best source of data for this purpose is household balance sheet (HBS) data, which are now provided by 50 countries, although 25 of these countries cover only financial assets and debts [...] the results are supplemented by econometric techniques, which generate estimates of the level of wealth in countries that lack direct information for one or more years.

The second step involves constructing the pattern of wealth holdings within nations. We use direct data on the distribution of wealth for 37 countries. Inspection of data for these countries suggests a relationship between wealth distribution and income distribution, which can be exploited in order to provide an initial estimate of wealth distribution for the other 157 countries, which have data on income distribution but not on wealth ownership.

the third step makes use of the information in the Forbes world list of billionaires to adjust the wealth distribution pattern in the highest wealth ranges

comments powered by Disqus